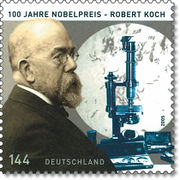

Robert Koch

| Robert Koch | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 11 December 1843 Clausthal, Kingdom of Hanover |

| Died | 27 May 1910 (aged 66) Baden-Baden, Grand Duchy of Baden |

| Fields | Microbiology |

| Institutions | Imperial Health Office, Berlin, University of Berlin |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Doctoral advisor | Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle |

| Known for | Discovery bacteriology Koch's postulates of germ theory Isolation of anthrax, tuberculosis and cholera |

| Influenced | Friedrich Loeffler |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Medicine (1905) |

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch (IPA: [kɔχ]; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician. He became famous for isolating Bacillus anthracis (1877), the Tuberculosis bacillus (1882) and the Vibrio cholerae (1883) and for his development of Koch's postulates. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his tuberculosis findings in 1905. He is considered one of the founders of microbiology, inspiring such major figures as Paul Ehrlich and Gerhard Domagk.

Contents |

Biography

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch was born in Clausthal, Germany as the son of a mining official. He studied medicine under Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle at the University of Göttingen and graduated in 1866. He then served in the Franco-Prussian War and later became district medical officer, Wollstein (Wolsztyn), Prussian Poland. Working with very limited resources, he became one of the founders of bacteriology, the other major figure being Louis Pasteur.

After Casimir Davaine showed the direct transmission of the anthrax bacillus between cows, Koch studied anthrax more closely. He invented methods to purify the bacillus from blood samples and grow pure cultures. He found that, while it could not survive outside a host for long, anthrax built persisting endospores that could last a long time.

These endospores, embedded in soil, were the cause of unexplained "spontaneous" outbreaks of anthrax. Koch published his findings in 1876,[1] and was rewarded with a job at the Imperial Health Office in Berlin in 1880. In 1881, he urged the sterilization of surgical instruments using heat.

In Berlin, he improved the methods he used in Wollstein, including staining and purification techniques, and bacterial growth media, including agar plates (thanks to the advice of Angelina and Walther Hesse) and the Petri dish, named after its inventor, his assistant Julius Richard Petri. These devices are still used today. With these techniques, he was able to discover the bacterium causing tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) in 1882 (he announced the discovery on 24 March). Tuberculosis was the cause of one in seven deaths in the mid-19th century.

In 1883, Koch worked with a French research team in Alexandria, Egypt, studying cholera. Koch identified the vibrio bacterium that caused cholera, though he never managed to prove it in experiments. The bacterium had been previously isolated by Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini in 1854, but his work had been ignored due to the predominance of the miasma theory of disease. Koch was unaware of Pacini's work and made an independent discovery, and his greater preeminence allowed the discovery to be widely spread for the benefit of others. In 1965, however, the bacterium was formally renamed Vibrio cholera Pacini 1854.

In 1885, he became professor of hygiene at the University of Berlin, then in 1891 he was made Honorary Professor of the medical faculty and Director of the new Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (eventually renamed as the Robert Koch Institute), a position from which he resigned in 1904. He started traveling around the world, studying diseases in South Africa, India, and Java. He visited what is now called the Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Mukteshwar on request of the then Government of India to investigate on cattle plague. The microscope used by him during that period was kept in the museum maintained by IVRI.

Probably as important as his work on tuberculosis, for which he was awarded a Nobel Prize (1905), are Koch's postulates, which say that to establish that an organism is the cause of a disease, it must be:

- found in all cases of the disease examined

- prepared and maintained in a pure culture

- capable of producing the original infection, even after several generations in culture

- retrievable from an inoculated animal and cultured again.

Koch's pupils found the organisms responsible for diphtheria, typhoid, pneumonia, gonorrhoea, cerebrospinal meningitis, leprosy, bubonic plague, tetanus, and syphilis, among others, by using his methods.

Robert Koch died on 27 May 1910 from a heart-attack in Baden-Baden, aged 66.

Honors and awards

The crater Koch on the Moon is named after him. The Robert Koch Prize and Medal were created to honour Microbiologists who make groundbreaking discoveries or who contribute to global health in a unique way. The now-defunct Robert Koch Hospital at Koch, Missouri (south of St. Louis, Missouri), was also named in his honor. A hagiographic account of Koch's career can be found in the 1939 Nazi propaganda film Robert Koch, der Bekämpfer des Todes (The fighter against death), directed by Hans Steinhoff and starring Emil Jannings as Koch.

Because the construction efforts were jeopardized by malaria outbreaks on Veliki Brijun Island which occurred during summer months and even Kupelwieser himself fell ill with the disease.[2], so at the turn of the century, the Austrian steel industrialist Paul Kupelweiser had invited the famous physician Robert Koch, who at the time studied different forms of malaria and quinine-based treatments. Koch accepted the invitation and spent two years, from 1900 to 1902, on the Brijuni Islands Archipelago.[2]

According to Koch’s instructions, all the ponds and swamps where malaria-carrying mosquitoes hatched were reclaimed and patients were treated with quinine. Malaria was thus eradicated by 1902 and Kupelwieser erected a monument to Koch, which still stands in vicinity of the 15th century Church of St. German on Veliki Brijun Island.

See also

- German inventors and discoverers

References

- ↑ Koch, R. (1876) "Untersuchungen über Bakterien: V. Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus anthracis" (Investigations into bacteria: V. The etiology of anthrax, based on the ontogenesis of Bacillus anthracis), Cohns Beitrage zur Biologie der Pflanzen, vol. 2, no. 2, pages 277-310.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fatović-Ferenčić, Stella (June 2006). "Brijuni Archipelago: Story of Kupelwieser, Koch, and Cultivation of 14 Islands". Croatian Medical Journal. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2121595/. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Robert Koch and the Institute". Robert Koch Institute. 2004-11-30. http://www.rki.de/cln_011/nn_231522/EN/Content/Institute/History/Robert__Koch.html__nnn=true. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- Brock, Thomas D. (1999). Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. ISBN 9781555811433. OCLC 39951653.

- Morris, Robert D (2007). The blue death: disease, disaster and the water we drink. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 9780060730895. OCLC 71266565.

- Gradmann, Christoph (2009). Laboratory Disease: Robert Koch's Medical Bacteriology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9870801893131.

External links

- Robert Koch Biography at the Nobel Foundation website

- MPIWG-Berlin, Robert Koch Biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Musoptin.com, original microscope out of the laboratory Robert Koch used in Wollstein (1877)

- Musoptin.com, microscope objectives: as they were used by Robert Koch for his first photos of microorganisms (1877–1878)

|

||||||||